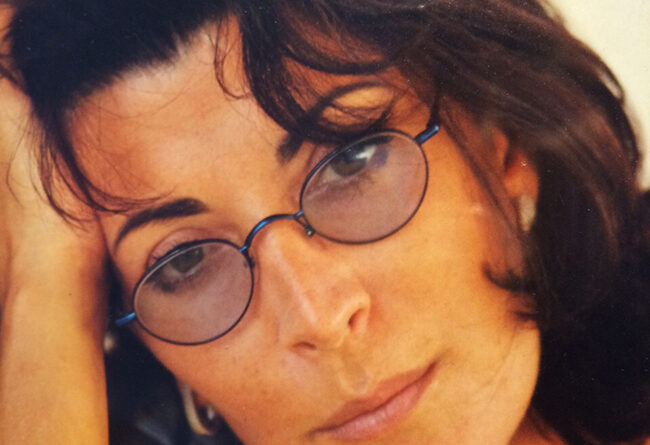

Interview with the Psychoanalyst Mona Boutaleb

Hello Mrs. Boutaleb, to begin our interview I would like to ask you to introduce your professional career

I am a Psychoanalyst, Doctor of psychopathology and University degree teacher at the University Jean Jaurès in Toulouse.

I have a studio in private practice and I cooperate with various public institutions in France.

The theme of our interview is melancholy, you can give a definition of this disease?

The story begins at the dawn of the fourth century BC., In Greece, where it appears for the first time the word “melankholia”. The term is composed of Khula (bile) and Melas (black), literally “black bile”. The human being was thought according to the laws of nature, which followed the four seasons. Hence, the four “humors” are isolated in the human body: black bile (melancholy), yellow bile, phlegm and blood.

The body was indeed considered healthy if the balance of these four humors was satisfied. This means that the disease can be defined as the preponderance of a mood than the other. Black bile or melancholy, represents both the natural substance in the body and the disease related to the excess of this substance. Since then, the concept of melancholy has spanned the centuries integrating from time to time with the epistemological context of each era. In other words one should consider the melancholy positively or negatively depending on the dominant thought or approach to the human being in the different eras.

The emotion of sadness and fear are recalled in a first attempt to clinical description of the disease, however, this description will be quickly overtaken by a second definition of a philosophical approach, presumably amenable to a text attributed to Aristotle (“Problem XXX”), where the melancholic is personified by the genius.

In his “Treatise on divination” Aristotle describes a tendency to be guided by your imagination. The melancholic can sometimes show a delirious imagination (today we would say that the melancholic looses the sense of reality). Aristotle considers that this imagination is fruitful for the creation of poetry. Hence the various states that the melancholic faces, are similar to those that the poet himself faces and that are the base of the truth of his work. Aristotle and his followers show that melancholy comes both from the body and from the soul. The challenge with this approach is nothing less than the unity of life, the eventual union of body and soul. Unlike Plato where dualism opposes and dissociates the soul and the body.

And because melancholy is conducive to both the talent and the madness, the bad mood is no longer a divine curse, but a kind of gift that man does to himself by depriving reason.

There would be only a small difference of degree between the insane and the genius, between delirium and inspiration.

In conclusion with Aristotle melancholy is clearly associated to the imagination, the black bile of “Problem XXX” is a metaphor of the imagination that becomes a physiological foundation.

It will be the Age of Enlightenment that will rock the melancholy towards the side of unreasonableness.

The desire to overcome obscurantism and promote knowledge will not leave room for the fervid imagination of melancholic, which will be assimilated to madness.

Towards the end of the twentieth century, we find only scattered and ironic allusions to the iconography of melancholy. And classical psychiatry will continue this paradigmatic transformation to finally integrate it as a clinical entity in the field of abnormality.

In our age, modern psychiatry calls melancholy the most advanced form of depression, by designating a serious illness, leaving any further delay to consider it as a disease, with full medical sense.

The term does not apply to a vague sadness without definite cause, but a psychosis that occurs in episodes characterized by, as stated by the German psychiatrist Wilhelm Griesinger: “the existence of a morbid painful feeling, depressed, which dominates the subject” In its simplest form, this pain is a vague sense of oppression, anxiety and sadness.

Other psychiatric concepts will define melancholy globally as a state of intense depression lived with a sense of pain characterized by a slow inhibition of mental and psychomotor functions. A deep depressed mood that would be characterized by: psychomotor inhibition, intense moral pain with despair, severe anxiety with depreciation of oneself, delusions regarding worthlessness, guilt, or the ruin with a high risk of suicide.

Some consider melancholy the disease of the 21st century, what do you think about this?

I think this disease that has existed for over two thousand years can not be characterized by the century in which we live, but it seems that the age in which we live exacerbates it. Let me explain: the civilization in which we live creates discomfort (in the Freudian sense – “Civilization and Its Discontents”), giving the melancholy, the ability to to adorn its finest assets. By this I mean that the form of the social bond that tends to dominate today, requires the conception of rationality, of an infallible mode of knowledge. Therefore, it occurs in our time the idea of an organization that would eliminate all forms of otherness, the idea of an organization that would like for everyone. This is why the globalization of the market agrees to the ‘air du temps’.

But this leads to two pitfalls that articulate poorly with each other: the first is to force people to dissolve into the mass, to give up their individuality, for assimilation, arrangement or adaptation, and the second is to make social life impossible with the pretext of respecting the individuality – to each his own truth, to each his freedom, to each his own way of enjoying life.

Discomfort, created by our society, thus leads the human subject to “fabricate” his symptom as the manifestation of his protest more intimate and singular.

This symptom allows him to “save himself” in some way, to avoid to melt into a mass that can only promise the non-existence of his unique being.

To illustrate what has just been said, it should be remembered a phrase of Montaigne, regarding melancholy. Visiting the Italian poet Torquato Tasso, a melancholic by nature, and alarmed by the effects of this evil, he nevertheless praised the withdrawal within oneself to which it invites, in a “secret place where the soul withdraws, to keep itself in eternal serenity.”

I wonder, I am often sad, am I depressed? Melancholy requires drugs? You talk about psychoanalysis, what does it imply?

Melancholy is a psychological suffering, a moral pain, which results in episodes of great desperation where the subject says: “I am dead.” Freud speaks extensively about it in “Mourning and Melancholia,” where he compares melancholy to mourning, explaining that the mourning then takes a pathological form. Jacques Lacan, French psychoanalyst, in his seminar “Ethics”, talks about a man who, at this level, places himself in a position that he is his own death. Because at its most intense, the most extreme pain is the fact that one cannot feel anything anymore. The melancholy in the psychoanalytic sense is not a depression in the sense that we can not try to “drown” the first term in a generic form that includes the second. Because in this case, the clinical method would lose its accuracy, relevance and efficiency.

In the medical sense, melancholy can be seen as a depression because the chemical molecule that should heal it includes all forms of psychological suffering and makes no difference between each. So you see that the answer is different depending on the paradigm that we have chosen to adopt.

We must also point out that the current psychiatry hardly takes anymore into consideration the word of the patient. Psychoanalysis can not agree on this, having to see that unfortunately the psychic care is reduced more and more to a technique, an anomaly that must be eradicated at all costs, silencing the patient with drugs.

Psychoanalysis continues to defend the necessary craftmanship dimension, considering it is addressed to a being endowed with speech.

This is what implies psychoanalysis: the clinic of a subject that speaks to say what is being addressed in the reality of what it is, as a human being. The psychoanalyst accompanies the melancholic subject in the manifestations of this reality put into words, a reality that takes sense along the treatment.

I know that you started writing a book on melancholy recently. Could you tell us more?

In fact, I think it’s important to “refresh” the treatment of melancholy and say a little more about how this disease is treated in our century.

But for this we must wait for the official publication of the essay …